Tag Archives: insulators

Electric Charges

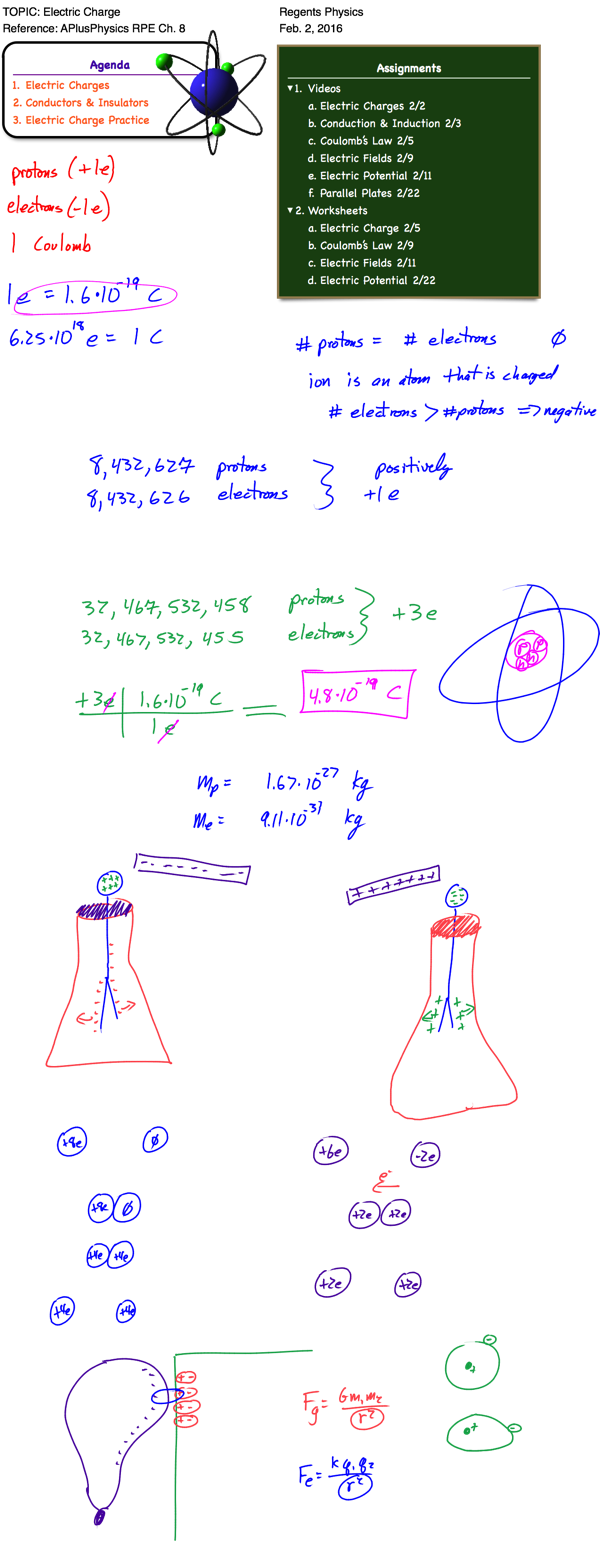

Matter is made up of atoms. Once thought to be the smallest building blocks of matter, we now know that atoms can be broken up into even smaller pieces, known as protons, electrons, and neutrons. Each atom consists of a dense core of positively charged protons and uncharged (neutral) neutrons. This core is known as the nucleus. It is surrounded by a “cloud” of much smaller, negatively charged electrons. These electrons orbit the nucleus in distinct energy levels. To move to a higher energy level, an electron must absorb energy. When an electron falls to a lower energy level, it gives off energy.

Most atoms are neutral — that is, they have an equal number of positive and negative charges, giving a net charge of 0. In certain situations, how- ever, an atom may gain or lose electrons. In these situations, the atom as a whole is no longer neutral and we call it an ion. If an atom loses one or more electrons, it has a net positive charge and is known as a positive ion. If, instead, an atom gains one or more electrons, it has a net negative charge and is therefore called a negative ion. Like charges repel each other, while opposite charges attract each other. In physics, we represent the charge on an object with the symbol q.

Charge is a fundamental measurement in physics, much as length, time, and mass are fundamental measurements. The fundamental unit of charge is the Coulomb [C], which is a very large amount of charge. Compare that to the magnitude of charge on a single proton or electron, known as an elemen- tary charge, which is equal to 1.6×10-19 coulomb. It would take 6.25×1018 elementary charges to make up a single coulomb of charge! (Don’t worry about memorizing these values, they’re listed for you on the front of the reference table).

Conductors and Insulators

Certain materials allow electric charges to move freely. These are called conductors. Examples of good conductors include metals such as gold, copper, silver, and aluminum. In contrast, materials in which electric charges can- not move freely are known as insulators. Good insulators include materials such as glass, plastic, and rubber. Metals are better conductors of electricity compared to insulators because metals contain more free electrons.

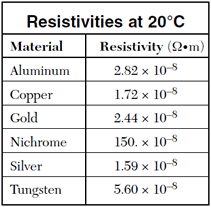

Conductors and insulators are characterized by their resistivity, or ability to resist movement of charge. Materials with high resistivities are good insula- tors. Materials with low resistivities are good conductors.

Semiconductors are materials which, in pure form, are good insulators. However, by adding small amounts of impurities known as dopants, their resistivities can be lowered significantly until they become good conductors.

Charging by Conduction

Materials can be charged by contact, or conduction. If you take a balloon and rub it against your hair, some of the electrons from the atoms in your hair are transferred to the balloon. The balloon now has extra electrons, and therefore has a net negative charge. Your hair has a deficiency of electrons, therefore it now has a net positive charge.

Much like momentum and energy, charge is also conserved. Continuing our hair and balloon example, the magnitude of the net positive charge on your hair is equal to the magnitude of the net negative charge on the balloon. The total charge of the hair/balloon system remains zero (neutral). For ev- ery extra electron (negative charge) on the balloon, there is a correspond- ing missing electron (positive charge) in your hair. This known as the law of conservation of charge.

Conductors can also be charged by contact. If a charged conductor is brought into conduct with an identical neutral conductor, the net charge will be shared across the two conductors.

Question: If a conductor carrying a net charge of 8 elementary charges is brought into contact with an identical conductor with no net charge, what will be the charge on each conductor after they are separated?

Answer: Each conductor will have a charge of 4 elementary charges.

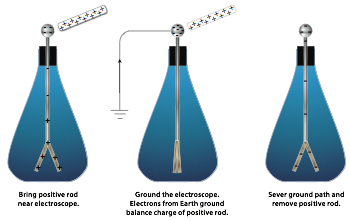

Electroscope

A simple tool used to detect small electric charges known as an electroscope functions on the basis of conduction. The electroscope consists of a conducting rod attached to two thin conducting leaves at one end and isolated from surrounding charges by an insulating stopper placed in a flask. If a charged object is placed in contact with the conducting rod, part of the charge is transferred to the rod. Because the rod and leaves form a conducting path and like charges repel each other, the charges are distributed equally along the entire rod and leaf apparatus. The leaves, having like charges, repel each other, with larger charges providing greater leaf separation!

Charging by Induction

Conductors can also be charged without coming into contact with another charged object in a process known as charging by induction. This is accomplished by placing the conductor near a charged object and grounding the conductor. To understand charging by induction, you must first realize that when an object is connected to the earth by a conducting path, known as grounding, the earth acts like an infinite source for providing or accepting excess electrons.

To charge a conductor by induction, you first bring it close to another charged object. When the conductor is close to the charged object, any free electrons on the conductor will move toward the charged object if the object is positively charged (since opposite charges attract) or away from the charged object if the object is negatively charged (since like charges repel).

If the conductor is then “grounded” by means of a conducting path to the earth, the excess charge is compensated for by means of electron transfer to or from earth. Then the ground connection is severed. When the originally charged object is moved far away from the conductor, the charges in the conductor redistribute, leaving a net charge on the conductor as shown.

You can also induce a charge in a charged region in a neutral object by bringing a strong positive or negative charge close to that object. In such cases, the electrons in the neutral object tend to move toward a strong positive charge, or away from a large negative charge. Though the object itself remains neutral, portions of the object are more positive or negative than other parts. In this way, you can attract a neutral object by bringing a charged object close to it, positive or negative. Put another way, a positively charged object can be attracted to both a negatively charged object and a neutral object, and a negatively charged object can be attracted to both a positively charged object and a neutral object.

For this reason, the only way to tell if an object is charged is by repulsion. A positively charge object can only be repelled by another positive charge and a negatively charged object can only be repelled by another negative charge.

Resistance of a Wire

Resistance

Electrical charges can move easily in some materials (conductors) and less freely in others (insulators), as we learned previously. We describe a material’s ability to conduct electric charge as conductivity. Good conductors have high conductivities. The conductivity of a material depends on:

- Density of free charges available to move

- Mobility of those free charges

In similar fashion, we describe a material’s ability to resist the movement of electric charge using resistivity, symbolized with the Greek letter rho (![]() ). Resistivity is measured in ohm-meters, which are represented by the Greek letter omega multiplied by meters (

). Resistivity is measured in ohm-meters, which are represented by the Greek letter omega multiplied by meters (![]() •m). Both conductivity and resistivity are properties of a material.

•m). Both conductivity and resistivity are properties of a material.

When an object is created out of a material, the material’s tendency to conduct electricity, or conductance, depends on the material’s conductivity as well as the material’s shape. For example, a hollow cylindrical pipe has a higher conductivity of water than a cylindrical pipe filled with cotton. However, shape of the pipe also plays a role. A very thick but short pipe can conduct lots of water, yet a very narrow, very long pipe can’t conduct as much water. Both geometry of the object and the object’s composition influence its conductance.

Focusing on an object’s ability to resist the flow of electrical charge, we find that objects made of high resistivity materials tend to impede electrical current flow and have a high resistance. Further, materials shaped into long, thin objects also increase an object’s electrical resistance. Finally, objects typically exhibit higher resistivities at higher temperatures. We take all of these factors together to describe an object’s resistance to the flow of electrical charge. Resistance is a functional property of an object that describes the object’s ability to impede the flow of charge through it. Units of resistance are ohms (![]() ).

).

For any given temperature, we can calculate an object’s electrical resistance, in ohms, using the following formula, which can be found on your reference table.

![]()

In this formula, R is the resistance of the object, in ohms (![]() ), rho (

), rho (![]() ) is the resistivity of the material the object is made out of, in ohm*meters (

) is the resistivity of the material the object is made out of, in ohm*meters (![]() •m), L is the length of the object, in meters, and A is the cross-sectional area of the object, in meters squared. Note that a table of material resistivities for a constant temperature is given to you on the reference table!

•m), L is the length of the object, in meters, and A is the cross-sectional area of the object, in meters squared. Note that a table of material resistivities for a constant temperature is given to you on the reference table!

Let’s try a sample problem calculating the electrical resistance of an object:

Question: A 3.50-meter length of wire with a cross-sectional

area of 3.14 × 10–6 m2 at 20° Celsius has a resistance of 0.0625. Determine the resistivity of the wire and the material it is made out of.

Answer:

Introduction to Electrostatics

Building Blocks of Matter

Matter is made up of atoms. Once thought to be the smallest building blocks of matter, we now know that atoms can be broken up into even smaller pieces, known as protons, electrons, and neutrons. Each atom consists of a dense core of positively charged protons and uncharged (neutral) neutrons. This core is known as the nucleus. It is surrounded by a “cloud” of much smaller, negatively charged electrons. These electrons orbit the nucleus in distinct energy levels. To move to a higher energy level, an electron must absorb energy. When an electron falls to a lower energy level, it gives off energy.

Most atoms are neutral — that is, they have an equal number of positive and negative charges, giving a net charge of 0. For this to occur, the number of protons must equal the number of electrons. In certain situations, however, an atom may gain or lose electrons. In these cases, the atom as a whole is no longer neutral, and we call it an ion. If an atom loses one or more electrons, it has a net positive charge, and is known as a positive ion. If, instead, an atom gains one or more electrons, it has a net negative charge, and is therefore called a negative ion. Like charges repel each other, while opposite charges attract each other. In physics, we represent the charge on an object with the symbol q.

Charge is a fundamental measurement in physics, much as length, time, and mass are fundamental measurements. The fundamental unit of charge is the Coulomb [C], which is a very large amount of charge. Compare that to the magnitude of charge on a single proton or electron, known as an elementary charge, which is equal to 1.6*10^-19 coulomb. It would take 6.25*10^18 elementary charges to make up a single coulomb of charge! (Don’t worry about memorizing these values, they’re listed for you on the front of the reference table!).

Question: An object possessing an excess of 6.0*10^6 electrons has what net charge?

Answer:

Conductors and Insulators

Certain materials allow electric charges to move freely. These are called conductors. Examples of good conductors include metals such as gold, copper, silver, and aluminum. In contrast, materials in which electric charges cannot move freely are known as insulators. Good insulators include materials such as glass, plastic, and rubber.

Conductors and insulators are characterized by their resistivity, or ability to resist movement of charge. Materials with high resistivities are good insulators. Materials with low resistivities are good conductors.

Semiconductors are materials which, in pure form, are good insulators. However, by adding small amounts of impurities known as dopants, their resistivities can be lowered significantly until they become good conductors.

Charging by Conduction

Materials can be charged by contact, or conduction. If you take a balloon and rub it against your hair, some of the electrons from the atoms in your hair are transferred to the balloon. The balloon now has extra electrons, and therefore has a net negative charge. Your hair has a deficiency of electrons, therefore it now has a net positive charge.

Much like momentum and energy, charge is also conserved. Continuing our hair and balloon example, the magnitude of the net positive charge on your hair is equal to the magnitude of the net negative charge on the balloon. The total charge of the hair/balloon system remains zero (neutral). For every extra electron (negative charge) on the balloon, there is a corresponding missing electron (positive charge) in your hair. This known as the law of conservation of charge.

Conductors can also be charged by contact. If a charged conductor is brought into conduct with an identical neutral conductor, the net charge will be shared across the two conductors.

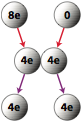

Question: If a conductor carrying a net charge of 8 elementary charges is brought into contact with an identical conductor with no net charge, what will be the charge on each conductor after they are separated?

Answer: Each conductor will have a charge of 4 elementary charges.

Question: What is the net charge (in coulombs) on each conductor after they are separated?

Answer:

Coulomb’s Law

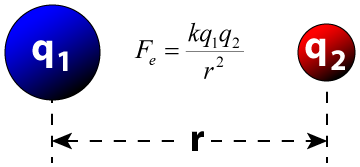

We know that like charges repel, and opposite charges attract. In order for charges to repel or attract, they apply a force upon each either. Similar to the manner in which the force of attraction between two masses is determined by the amount of mass and the distance between the masses, as described by Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation, the force of attraction or repulsion is determined by the amount of charge and the distance between the charges. The magnitude of the electrostatic force is described by Coulomb’s Law.

Coulomb’s Law states that the magnitude of the electrostatic force (Fe) between two objects is equal to a constant, k, multiplied by each of the two charges, q1 and q2, and divided by the square of the distance between the charges (r2). The constant k is known as the electrostatic constant, and is given on the reference table as: ![]() .

.

![]()

Notice how similar this formula is to the formula for the gravitational force! Both Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation and Coulomb’s Law follow the inverse-square relationship, a pattern that repeats many times over in physics. The further you get from the charges, the weaker the electrostatic force. If you were to double the distance from a charge, you would quarter the electrostatic force on a charge.

Formally, a positive value for the electrostatic force indicates that the force is a repelling force, while a negative value for the electrostatic force indicates that the force is an attractive force. Because force is a vector, you must assign a direction to it. To determine the direction of the force vector, once you have calculated its magnitude, use common sense to tell you the direction on each charged object. If the objects have opposite charges, they are being attracted, and if they have like charges, they must be repelling each other.

Question: Three protons are separated from a single electron by a distance of 1*10^-6 m. Find the electrostatic force between them. Is this force attractive or repulsive?

Answer: