Tag Archives: Voltage

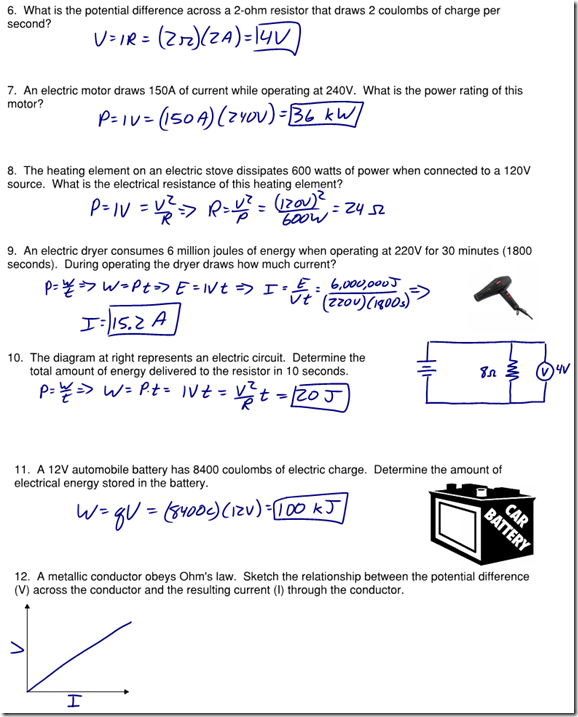

Electricity Refresher Solutions

Ohm’s Law

Agenda:

- Ohm’s Law

- Ohm’s Law Lab

If resistance opposes current flow, and potential difference promotes current flow, it only makes sense that these quantities must somehow be related. George Ohm studied and quantified these relationships for conductors and resistors in a famous formula now known as Ohm’s Law:

![]()

Ohm’s Law may make more qualitative sense if we re-arrange it slightly:

![]()

Now it’s easy to see that the current flowing through a conductor or resistor (in amps) is equal to the potential difference across the object (in volts) divided by the resistance of the object (in ohms). If you want a large current to flow, you would require a large potential difference (such as a large battery), and/or a very small resistance.

Question: The current in a wire is 24 amperes when connected to a 1.5 volt battery. Find the resistance of the wire.

Answer:

Note: Ohm’s Law isn’t truly a law of physics — not all materials obey this relationship. It is, however, a very useful empirical relationship that accurately describes key electrical characteristics of conductors and resistors. One way to test if a material is ohmic (if it follows Ohm’s Law) is to graph the voltage vs. current flow through the material. If the material obeys Ohm’s Law, you’ll get a linear relationship, and the slope of the line is equal to the material’s resistance.

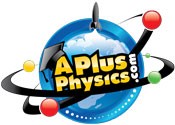

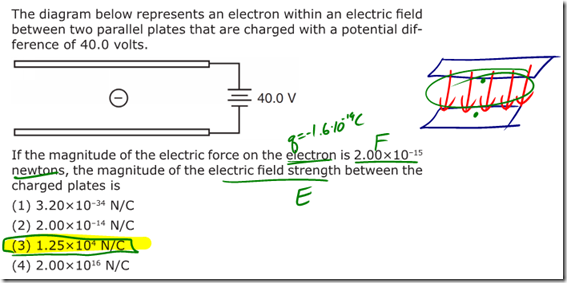

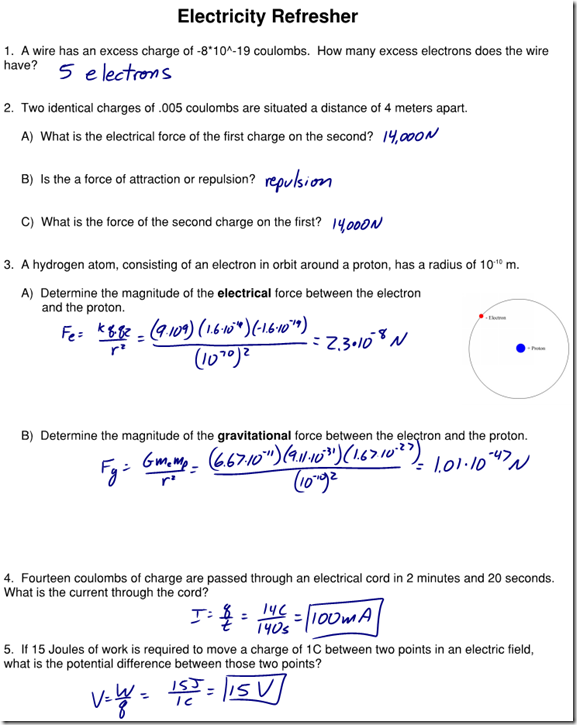

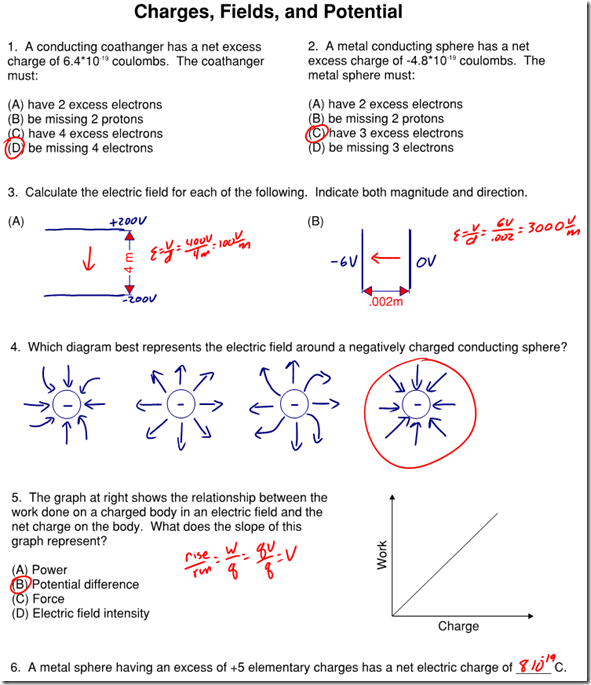

Electrostatics Problem Solving

Agenda:

Review HW: Charges, Fields and Potential

Video: Electrostatics Review

HANDOUT: Cartoon Charges

HW: Charges, Fields and Potential Packet (due 2/11) –> Solutions below

EXAM: P1, 4, 7 on Friday P8/9 on Thursday

Electric Potential Difference

Reminder: P1, 4, 7 Exam 2/11; P9 Exam 2/10

Electric Potential Difference

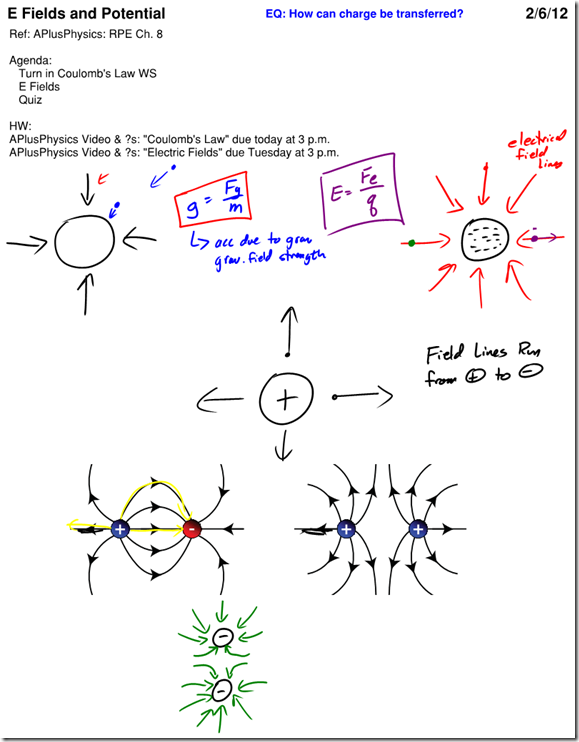

When we lifted an object against the force of gravity by applying a force over a distance, we did work to give that object gravitational potential energy. The same concept applies to electric fields as well. If you move a charge against an electric field, you must apply a force for some distance, therefore you do work and give it electrical potential energy. The work done per unit charge in moving a charge between two points in an electric field is known as the electric potential difference, (V). The units of electric potential are volts, where a volt is equal to 1 Joule per Coulomb. Therefore, if you did 1 Joule of work in moving a charge of 1 Coulomb in an electric field, the electric potential difference between those points would be 1 volt. This is given to you in the reference table as:

![]()

V in this formula is potential difference (in volts), W is work or electrical energy (in Joules), and q is your charge (in Coulombs). Let’s take a look at a sample problem.

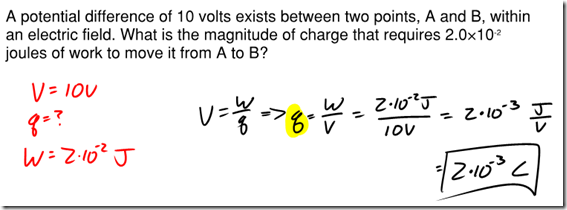

Question: A potential difference of 10.0 volts exists between two points, A and B, within an electric field. What is the magnitude of charge that requires 2.0 × 10–2 joule of work to move it from A to B?

Answer:

When dealing with electrostatics, often times the amount of electric energy or work done on a charge is a very small portion of a Joule. Dealing with such small numbers is cumbersome, so physicists devised an alternate unit for electrical energy and work that can be more convenient than the Joule. This unit, known as the electron-volt (eV), is the amount of work done in moving an elementary charge through a potential difference of 1V. One electron-volt, therefore, is equivalent to one volt multiplied by one elementary charge (in Coulombs): 1 eV = 1.6*10-19 Joules.

Question: A charge of 2*10-3 C is moved through a potential difference of 10 volts in an electric field. How much work, in electron-volts, was required to move this charge?

Answer:

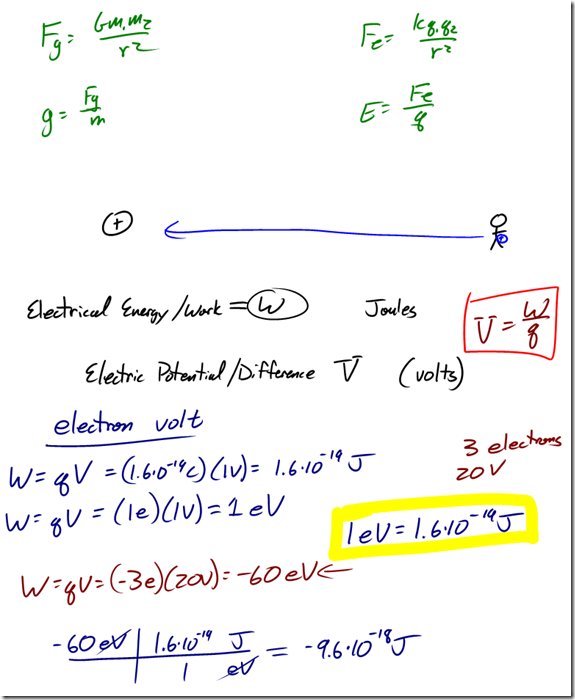

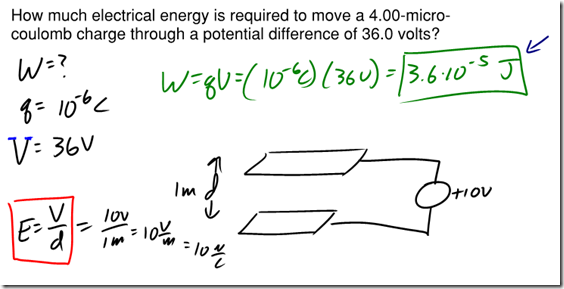

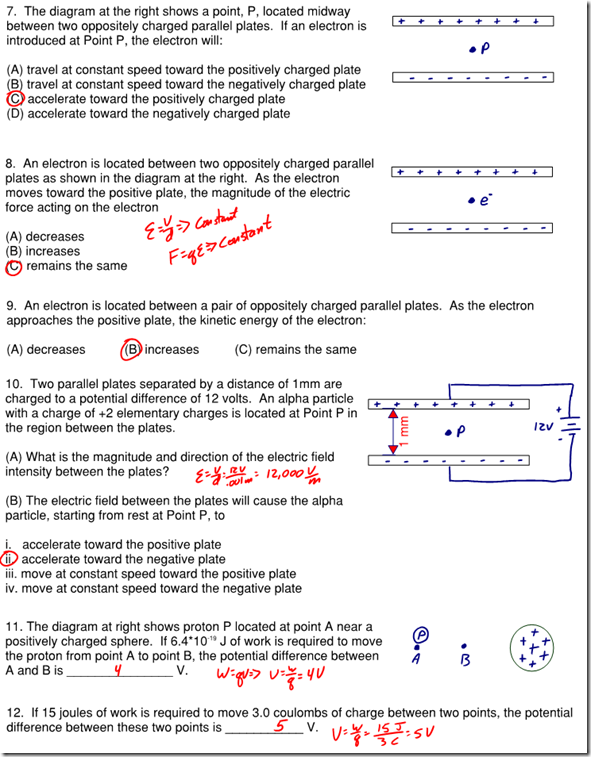

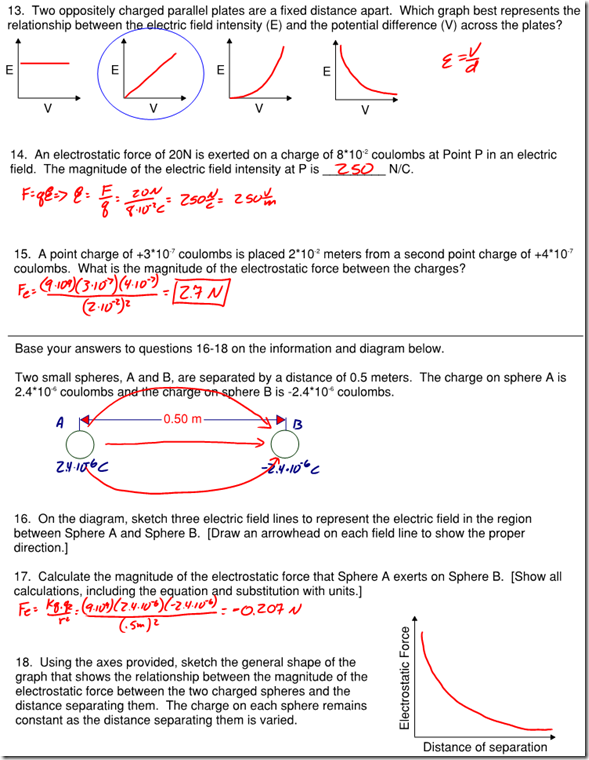

Parallel Plates

If you know the potential difference between two parallel plates, you can easily calculate the electric field strength between the plates. As long as you’re not near the edge of the plates, the electric field is constant between the plates, and its strength is given by:

![]()

You’ll note that with the potential difference V in volts, and the distance between the plates in meters, units for the electric field strength are volts per meter [V/m]. Previously, we stated that the units for electric field strength were newtons per Coulomb [N/C]. It is easy to show that these units are equivalent:

![]()

Question: Which electrical unit is equivalent to one joule?

- volt / meter

- ampere * volt

- volt / Coulomb

- Coulomb*volt

Answer: (4) Coulomb*volt

Let’s try another sample problem:

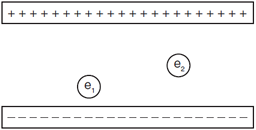

Question: The diagram represents two electrons, e1 and e2, located between two oppositely charged parallel plates. Compare the magnitude of the force exerted by the electric field on e1 to the magnitude of the force exerted by the electric field on e2.

Answer: The force is the same because the electric field is the same for both charges, as the electric field is constant between two parallel plates.

Equipotential Lines

Much like looking at a topographic map which shows you lines of equal altitude, or equal gravitational potential energy, we can make a map of the electric field and connect points of equal electrical potential. These lines, known as equipotential lines, always cross electrical field lines at right angles, and show positions in space with constant electrical potential. If you move a charged particle in space, and it always stays on an equipotential line, no work will be done.